When it comes to allergen labelling, a ‘may contain’ statement is your last line of defence, not your first. You should only ever reach for a precautionary allergen label (PAL) after a rigorous risk assessment proves there’s a genuine, unavoidable risk of an allergen sneaking into a product where it isn’t meant to be.

It’s a serious step, and it is not a substitute for having solid manufacturing and handling practices in place. Let’s break down what that means in practice.

You’ve seen the phrases: “may contain nuts,” “made in a factory that also handles milk.” This is precautionary allergen labelling. Its job is very specific: to flag a potential risk for people with severe food allergies, letting them know that the unintentional presence of an allergen is still a possibility with the best safety controls.

This is a world away from the mandatory allergen labelling that’s legally required in the UK. By law, you must clearly declare any of the 14 major allergens if they are intentionally added as an ingredient. That’s non-negotiable.

PAL is a voluntary warning. It’s the action you take when, and only when, you’ve done everything you can to prevent cross-contamination, but the risk just can’t be eliminated completely. Our comprehensive guide on food allergen labelling goes deeper into these fundamental requirements.

Getting your head around the difference is key for any food business. One protects consumers from known ingredients; the other protects them from unavoidable risks.

Here’s a real-world example:

This careful approach is central to food safety here in the UK. Since Natasha’s Law came into effect in October 2021, requiring full ingredient lists on all prepacked foods for direct sale, the scrutiny on all types of allergen communication has intensified.

Here’s a quick summary to give you a better sense of how these two types of labelling compare.

| Aspect | Mandatory Labelling (e.g. Natasha’s Law) | Precautionary Labelling (PAL) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To declare allergens intentionally present as ingredients. | To warn of a potential, unavoidable risk of allergen cross-contact. |

| Legal Status | Compulsory under UK food law. | Voluntary, but based on a formal risk assessment. |

| When to Use | Always, when one of the 14 major allergens is in the recipe. | Only when a risk of cross-contact has been identified and cannot be removed. |

| Consumer Action | Allows consumers to avoid products containing their specific allergen. | Helps highly sensitive consumers make an informed choice about an uncertain risk. |

| Wording | Must follow specific formatting rules (e.g., bolding in the ingredients list). | No legally defined wording, but phrases like “may contain” are common. |

A precautionary label should be the result of a detailed investigation, not a lazy, catch-all safety net.

The whole point of a PAL is to give truthful, accurate information to the allergic consumer, allowing them to make a safe and informed decision. Overusing it just creates noise and devalues the warning for those who need it most.

The decision to add a ‘may contain’ label lives and dies by your risk assessment. This isn’t just a box-ticking exercise. It means methodically mapping out every potential point of cross-contact, from shared air vents to scoops and storage areas. You need to evaluate how likely contamination is at each point and confirm that your control measures-like cleaning, scheduling, and staff training-are not enough to bring that risk down to zero.

Without that hard evidence, a ‘may contain’ statement is misleading. It’s a tool for transparency, but only when the risk is real.

Deciding to add a “may contain” label isn’t just a gut feeling; it’s the end result of a thorough and documented risk assessment. This process takes you out of the realm of guesswork and into a structured, evidence-based system that protects both your customers and your business.

Think of it as a methodical examination of your entire production line, designed to pinpoint exactly where things could go wrong. The assessment boils down to one fundamental question: where do allergens enter our facility, and where do they go from there? You need to map out every single touchpoint, from the moment a raw ingredient delivery arrives to the second the finished product is sealed in its packaging. This isn’t just about what’s in the recipe; it’s about the journey those ingredients take.

The first hands-on step is to get granular and identify every single place where allergen cross-contact could possibly occur. This means putting on your detective hat and thinking like an allergen particle that could drift, stick, or be carried anywhere.

In any food production environment, there are some usual suspects. Keep a sharp eye on these common hotspots:

A useful exercise is to physically trace the path of a high-risk ingredient, like peanuts, through your entire facility. Document every surface, piece of equipment, and person it encounters. This simple walkthrough often shines a light on risks you hadn’t even considered.

Once you’ve mapped out all the potential cross-contact points, the next stage is to evaluate the actual risk. This isn’t about just listing possibilities; it’s about assessing two key factors: the likelihood of contamination actually happening and the severity of the potential allergic reaction. For instance, the likelihood of airborne flour dust spreading is much higher than a properly sealed bag of almonds leaking.

Next, you have to take a hard, honest look at the control measures you already have in place. Are they truly enough to eliminate the risks you’ve identified? These controls might include:

A formal risk assessment is the backbone of responsible allergen management. It provides the documented evidence needed to justify a precautionary label, proving it’s a necessary warning, not a convenient cover-up.

This systematic approach is becoming non-negotiable. A 2022 UK Food Standards Agency consultation revealed that only about 50% of manufacturers conduct regular, formal allergen risk assessments. The consultation made it clear that PAL should be a last resort, reserved for genuine, scientifically assessed risks after all other control strategies have been tried and tested.

The goal is to figure out if your controls bring the risk down to an acceptable level. If, after implementing every reasonable control measure, a significant risk of cross-contact still remains, that is the precise moment when a precautionary allergen label becomes necessary. The documentation from this assessment is your justification. For a deeper look into current regulations, you can explore our other resources on food allergen labelling.

Knowing the theory behind PAL is one thing, but applying it on the factory floor is where things get real. Let’s walk through some common situations where, even after you’ve done everything else right, a precautionary label becomes the only responsible path forward.

This is a classic. Picture this: your facility runs a batch of pecan-topped carrot cake in the morning, then switches to a gluten-free victoria sponge in the afternoon on the same line. You have a fully validated, strong cleaning procedure between runs. But can you honestly guarantee 100% removal of every microscopic nut protein from the conveyor belts, mixers, and all the little nooks and crannies in the ovens?

If your risk assessment and scientific testing show that a trace amount could remain, that’s your trigger. A “may contain nuts” label isn’t an admission of failure; it’s a transparent warning to the consumer that a genuine, albeit small, risk exists.

Powdered ingredients are notoriously tricky. Imagine a large open-plan facility. On one side, milk powder is being measured and mixed for one product. Not too far away, a dairy-free, vegan chocolate bar is being packaged. That fine milk powder can become airborne, travel through ventilation systems, and settle on practically anything-other equipment, packaging materials, or the vegan product itself.

This kind of cross-contact is incredibly difficult to control completely. When you cannot contain the dust, you have to communicate the risk.

Your supply chain is a huge part of the puzzle. What do you do when one of your key ingredients arrives with its own precautionary allergen label?

Let’s say the cocoa powder you use for your signature biscuits comes from a supplier with a “may contain soya” warning on the sack. That risk does not just disappear when it enters your factory; it’s now your risk to manage. You cannot just ignore it. Your only options are to either conduct your own rigorous, batch-by-batch testing to prove the cocoa is soya-free or, more realistically, pass that warning on to your customers. It’s all about maintaining that chain of transparency.

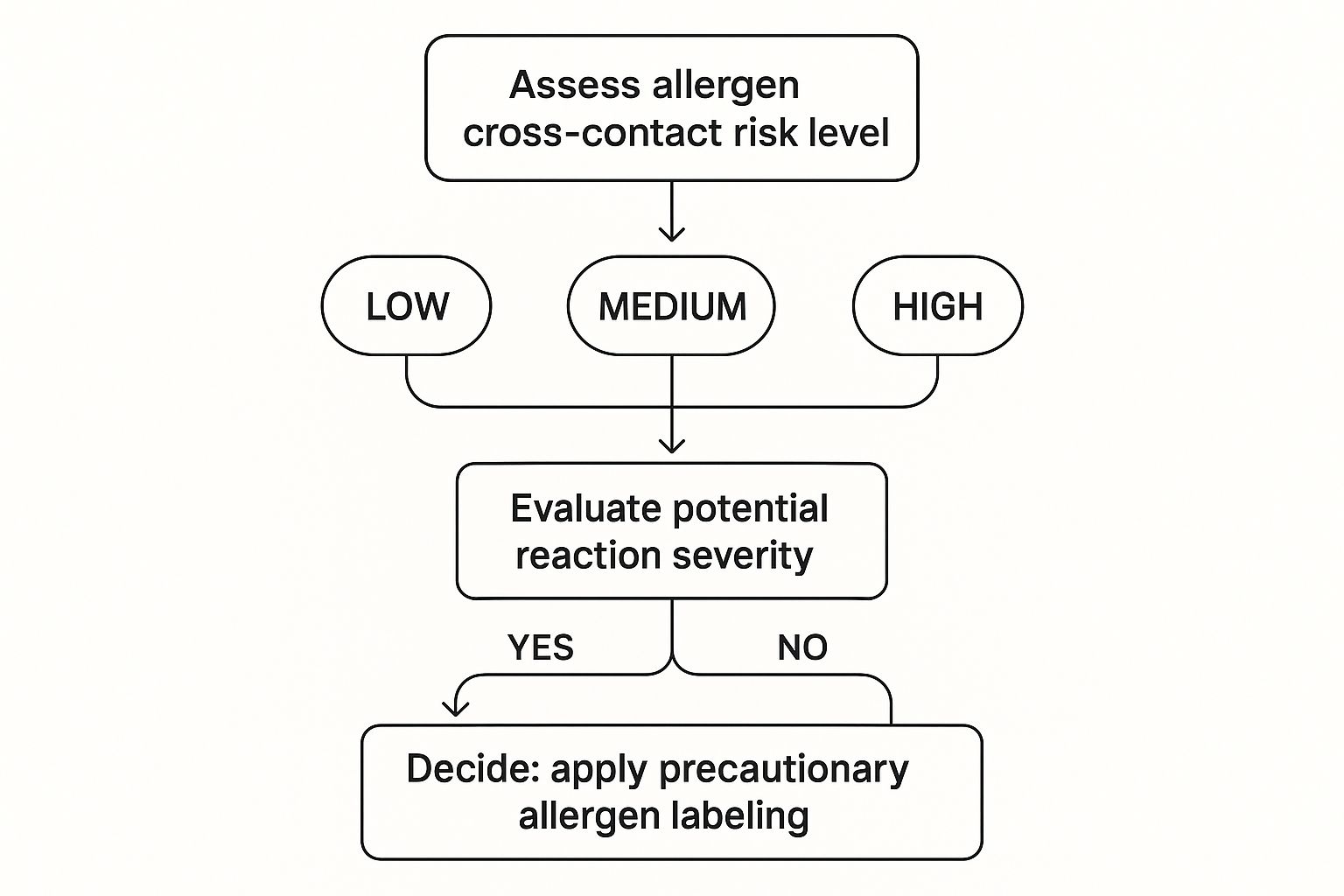

This is a great little visual to help map out the thought process.

It boils the decision down to three core questions: How likely is the cross-contact? How severe could the reaction be? Based on those answers, you make the call on labelling.

The decision to use a PAL comes from honestly acknowledging the limitations of your control measures. You can have the best GMPs in the world, but some risks are simply unavoidable.

Precautionary allergen labelling should only be used after a thorough risk assessment reveals a genuine, demonstrable, and uncontrollable risk of allergen cross-contact. It is the final safety net, not a substitute for proper allergen management.

I’ve put together a table showing how this thought process plays out in different situations.

This table breaks down a few common scenarios, detailing the risk, the controls in place, and the final justification for the labelling decision.

| Scenario | Identified Risk | Control Measures Applied | PAL Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bakery producing both almond croissants and plain croissants on the same workstation. | Cross-contact from almond flour dust and residues on surfaces and hands. | Segregated production times, thorough cleaning and sanitising of surfaces, and mandatory glove changes. | PAL Required (“May contain nuts”): Fine almond flour dust is airborne and difficult to contain 100%. The risk of trace residue remains. |

| Frying chips in the same oil previously used for battered fish (containing gluten and fish). | Allergen proteins from the batter and fish leaching into the cooking oil and transferring to the chips. | Regular oil filtering schedule is in place between different product types. | PAL Required (“May contain gluten, fish”): Standard filtering does not remove all dissolved proteins. The risk to a sensitive individual is significant and uncontrollable. |

| Packing shelled peanuts and then raisins on the same packaging line. | Peanut fragments or dust remaining in the weighing and bagging equipment after cleaning. | Line is disassembled, vacuumed, and deep-cleaned with validated swabbing tests between runs. | PAL Not Required: The risk assessment, supported by negative swab tests after cleaning, demonstrates the control measures are effective at eliminating the risk. |

| Using a supplier’s chocolate chips that carry a “may contain milk” warning. | The risk of milk protein cross-contact is inherited from the raw material supplier. | No in-house controls can remove an allergen already present in an ingredient. | PAL Required (“May contain milk”): The risk is present before the ingredient even enters the production process. The warning must be passed on to protect the consumer. |

Seeing it laid out like this highlights that the decision isn’t arbitrary. It’s a direct result of a careful and documented risk assessment process. In every case where PAL is used, it’s because a responsible business has identified a genuine risk it cannot eliminate and has chosen to be upfront about it.

While precautionary allergen labelling (PAL) is meant to be a helpful tool, its effectiveness completely falls apart when it’s used carelessly. Slapping a “may contain” statement on everything as a default safety net, rather than as a considered last resort, causes real problems for both shoppers and businesses.

It’s a move that can quickly undermine the very safety it’s supposed to protect.

One of the biggest issues is something called “warning fatigue.” Think about it: when consumers are bombarded with precautionary labels on a massive number of products, the warnings just become background noise. People with allergies might start to ignore them, figuring they’re just a legal disclaimer instead of a sign of genuine risk.

This desensitisation is dangerous. It can push someone to take a chance on a product that actually poses a real threat to their health.

From a business standpoint, overusing PAL can seriously damage your brand. It can come across as a lazy approach to allergen management, suggesting your company isn’t willing to invest in the proper cleaning, segregation, and risk assessment needed. This is where getting your food allergen labelling strategy right becomes crucial for building trust.

Instead of seeing you as a responsible manufacturer, customers might just see a business cutting corners.

The impact on consumer choice is also huge. For the estimated 2 million people in the UK with a diagnosed food allergy, an unnecessary “may contain” label snatches another safe option off the shelf. Every time a label is used without good reason, their world gets a little bit smaller.

A precautionary label should be a red flag for a real, unavoidable risk. When it becomes background noise, it fails the people who depend on it most and can signal poor manufacturing practices to everyone else.

The lack of a mandatory legal threshold for using PAL in the UK is a huge part of the problem. Without clear, unified rules, manufacturers are left to make their own judgement calls, and the results are all over the place.

This inconsistency breeds confusion and mistrust. Research shows that around 72% of UK consumers with food allergies find these labels confusing. One company’s “may contain nuts” might signal a high, proven risk, while another’s might be based on a purely theoretical possibility.

It creates a minefield for shoppers just trying to make safe choices for themselves and their families. You can read more about the research findings on precautionary allergen labelling and how it affects consumer trust.

Once you’ve gone through your risk assessment and decided a precautionary allergen label is unavoidable, your next job is to pick the right words. This isn’t a trivial step. The phrase you choose needs to clearly and honestly communicate the specific risk to your customers, but without causing unnecessary panic. How you phrase the warning shapes how someone with an allergy will view your product.

In the UK, there’s no single, legally required phrase for these labels. This flexibility can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it lets you tailor the message to your specific situation. On the other, it’s led to a lot of different phrases on the market, which can be confusing for shoppers trying to make a quick, safe decision.

Still, a few key phrases have become the unofficial industry standard.

The name of the game here is precision. A fuzzy, vague warning does not help anyone. You want to give a clear picture of why there might be a risk. Let’s break down the most common options and when you might use them.

Here’s a key takeaway: The Food Standards Agency’s own research shows that this jumble of different phrases is a massive source of confusion for consumers. A more standardised approach to wording is widely seen as the best way forward to help people with allergies feel more confident about their food choices.

So, how do you choose? Go back to your risk assessment. If the risk is all about shared equipment, “May contain” is probably the most honest and accurate choice. If it’s more of a general environmental risk, like airborne flour or nut dust in a facility, then “Made in a factory that handles” might fit better.

Always aim for the wording that gives the most truthful reflection of the situation. Remember, your label is a direct line of communication with someone whose health could depend on it.

When you’ve got the basics down, precautionary allergen labelling (PAL) can throw up some tricky questions. Let’s tackle some of the most common ones that food businesses grapple with.

This is a big one, and the short answer is no. In the UK, a ‘may contain’ statement isn’t legally mandatory.

This is a major point of difference from the 14 major allergens, which must be declared by law. Precautionary labelling is completely voluntary. It’s a decision driven entirely by your own risk assessment. If you’ve done the work and can prove there’s a genuine, unavoidable risk of allergen cross-contact, that’s when you should use a PAL statement to keep your customers informed. The decision hinges on solid evidence from your assessment, not a legal box-ticking exercise.

Absolutely. It might seem contradictory at first, but a product can be labelled as ‘vegan’ and still carry a ‘may contain milk’ warning. These two statements are speaking to different things.

This is critical information. For someone with a severe milk allergy, even the smallest trace can be dangerous. For someone choosing a vegan diet for ethical reasons, the product is still perfectly suitable.

The two labels don’t cancel each other out. The vegan claim reflects the intentional recipe, while the PAL statement communicates an unavoidable risk from the production environment. Both are key for different people to make safe, informed decisions.

For a more detailed breakdown of UK labelling regulations, our guide to food allergen labelling is a great place to dig deeper.

Think of your risk assessment as a living document, not a one-and-done task. It needs to be revisited regularly to stay accurate.

As a rule of thumb, you should be doing a full review of your PAL decisions at least once a year. You need to act much faster if anything in your operation changes.

You should trigger an immediate review whenever you have:

Keeping these assessments up-to-date is fundamental. It ensures your labels are truthful, which is how you protect both your customers and your business.

At Sessions UK, we know that getting the label right is the final, critical step. If you’re looking for a reliable and efficient way to apply these all-important labels, take a look at our range of professional labelling machines to find the right fit for your operation.

Copyright © 2026 Sessions Label Solutions Ltd.